The Mouse That Roared: Disney’s 100th Anniversary Marks a Century of Sound that ESPN Built On

ESPN has helped lead broadcast-sports audio innovation during its years under the Disney umbrella

Story Highlights

In October, 1923, Walt Disney and his brother Roy set up the Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio for their first animation efforts. Those “Alice Comedies” were quickly followed by a couple of silent ‘toons featuring a certain mouse who would finally gain lasting fame five years later with “Steamboat Willie,” one of the first cartoons with synchronized sound as well as one of the first animated shorts to feature a fully post-produced soundtrack.

Walt had been inspired by 1927’s The Jazz Singer, regarded as cinema’s first proper “talkie” film. He committed fully to synched sound — he mortgaged his house and sold his car to get the $5,000 the audio for the animated short cost, an enormous sum at the time — and never looked back. Coming decades would see Disney at the cutting edge of audio technology for visual media, including milestones like a three-channel system for Leopold Stokowski’s soundtrack for “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” segment of the landmark animation feature Fantasia in 1940.

ESPN Carries The Torch

It’s an audio torch that ESPN has been carrying since it was founded in 1979 and continued when it became part of the Disney fold in 1996, when the Mouse Factory acquired the sports network’s parent company ABC/Cap Cities. In that time, ESPN helped broadcast-sports audio through its various inflections, from mono to stereo, through various flavors of surround, and ultimately to the brink of immersive sound. Disney’s 100th anniversary is a good vantage point from which to look back at those audio iterations through the eyes and ears of those who helped lead it.

Henry Rousseau, ESPN’s recently retired senior operations specialist, who joined the fledgling network in 1981, recalls the first ESPN game broadcast in stereo, a Denver vs. Oakland USFL game in June, 1984, which he says went smoothly. Not every show did so in the early days, however. Of a particular 1990 MLB game working from a newly commissioned production control room adapted for stereo audio, he remembers, “We were working pretty much all through the night and we didn’t have a chance to really fax it out through the satellite. We did our first game and we got a call from our boss at the time, Bill Lamb, and he says, I’m not hearing the nat sounds. We traced it down and come to find out that the phase was reversed on the left channel! So in between a break, we go down there, literally switch the wires, and everything was fine. And that was [one of] our first forays into stereo and in learning how to fax properly at that time.”

The transition to stereo was in part driven by more music being incorporated into sports broadcasts at the time, as MTV, which launched in 1981 and which solidified television as a music medium.

“A lot of it had to do with the music,” says ESPN lead audio engineer Scott Pray, who joined the network as an A1 in 1984, before many of the legalities of the intersection of music and sports became clear. “In the early days [the network was] playing anything we could get our hands on. We would play like Huey Lewis & the News a lot of other groups that had some kind of a song that we could loop. And there was a competition as to who could loop the song the best and get it on the air. And that’s what we would play with our daily affiliate feeds and highlights. And it got so popular that we used to get calls from the groups themselves thanking us for putting ’em on the air.”

Stereo may have doubled the number of broadcast channels, but it was still a simpler time operationally, though everyone was still learning on the job.

“We actually had to worry about four channels, which was the stereo mix, and then we would always put the nat sound on channels three and four, but that was it,” says Rousseau. “We didn’t have to worry about international, so it was very, very simple. Edits were sometimes complicated, but the guys at that time, they didn’t worry about edits. They would just fix it, live on air, make their corrections, and move forward. So being only concerned with just four channels of audio made life very easy at that point.”

Pray added that when an international channel was needed, it was still mono, and there was always a mono channel backup at the ready.

“Now it’s hard to quantify now many channels of audio on transmission paths we put out,” he says. “but some days it can top 200 channels of audio that we actually send back to the network.”

The shift to stereo also produced some new opportunities for effects capture on the playing field.

“When we moved from mono to stereo, that gave us a little more space [in which] to put things,” explains Pray. “[With mono], everything was right down the middle: you were listening to your announcers straight in the middle, the music was in the middle, the effects were in the middle. There’s just no space there. But once we spread the effects out to left and right, the announcers were still [phantom] centered [but] that gave us a little extra space to hear those nat sounds better when the music comes in in stereo. You hear that there’s a little more separation between your announcers and your music and your effects. It’s not jammed all into that one middle channel.”

Pray and Rousseau both credit the late Ron Scalise, the network’s chief remote audio engineer in the 1990s, with a lot of the audio innovations that came during the stereo era, including innovations in the X Games, such as microphone placements under skateboard ramps, and who worked on a variety of projects such as Monday Night Football and NASCAR, and led early efforts into surround sound.

“In the early days he pushed the envelope, as did most all the A1s ones at ESPN in the beginning, being very innovative and always trying new stuff,” Pray says. “I think ESPN throughout its history has been one to try new audio captures. I can remember the X-ducer microphone Ronnie created for X Games [a mic without a diaphragm capsule, making it impervious to wind noise, the Winter X Games’ most persistent audio challenge], and mounting 30 mics under a skateboard ramp and stuff like that. I think we’ve always tried to push that envelope and try to take that next step to try to capture those sounds. And when we went to stereo, we kind of opened up some avenues for us to better capture those sounds. And of course always the ultimate goal for any of this is to give the viewer a better experience. I don’t necessarily want the viewer to say, Ooh, that was a cool sound. I just want the viewer to hear what they’re supposed to hear and not really notice what we’re doing.”

Surrounded

The shift to surround sound was iterative. Chris Strong, ESPN Director Specialist Operations, says it started with “circle surround” — a matrixed format developed by SRS Labs, later acquired by DTS — before moving to discrete 5.1.

“[Circle sound] was the precursor to full 5.1 because we were limited to a stereo signal and we didn’t have the transmission paths at that time to do to discrete 5.1,” Rousseau explains. (And not unlike the infrastructural challenges that immersive audio currently faces.) “We were doing matrix-encoded audio, using all this gear that Ron [Scalise] was able to wheel and deal with these vendors to get demo equipment that would end up in Scotty’s truck and would last a season. [Laugh]. And then I, on the other hand, would end up in the basement of one of the buildings of ESPN listening to the game and talking to Ronnie and Scotty, and he’s making changes live on the air while we were listening, trying to create the best sound possible for the viewer. This was like the late 1990s, about the same time we were moving towards HD (video). Going from analog to SDI initially afforded us a few extra channels, and that continued to open up additional bandwidth for audio. That’s what was what was driving it. We went from circle surround, then we went to DTS, and I know we went heavily with DTS in South Africa for the World Cup.”

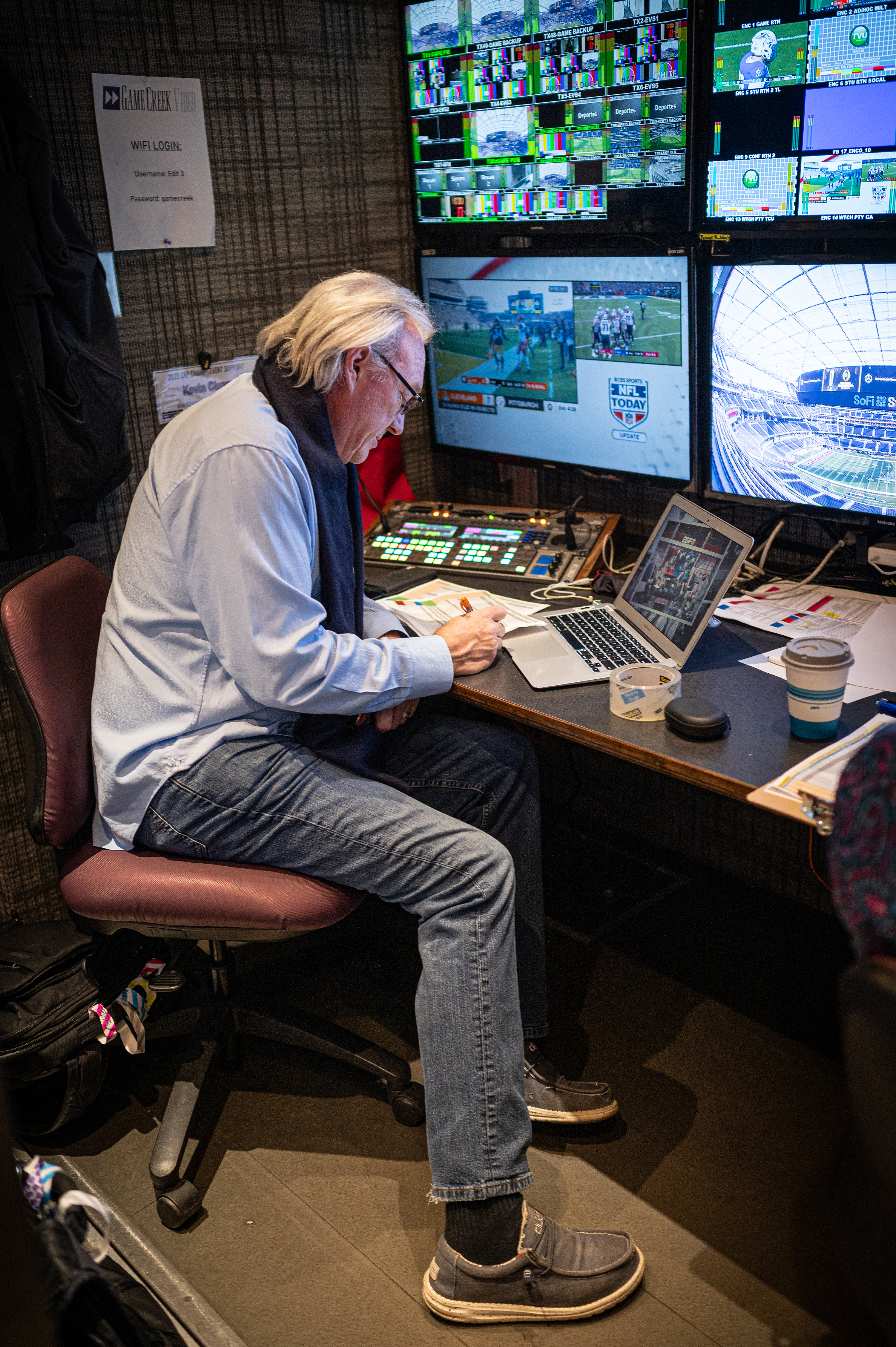

ESPN audio specialist Kevin Cleary prepares inside a Game Creek Video truck prior to the 2023 CFP National Championship. (Photo Courtesy of ESPN)

Rousseau says the first few years of surround sound were taken up with developing workflow patterns, best practices, and media archiving while also maintaining a robust stereo signal, all while keeping an eye and ear on how competing sports networks were also moving towards surround.

“Purists would say that you had to have individual channels, individual mic placements for 5.1, but in the early days, a lot of people were doing matrix audio and just steering it in such a way that it would be encoded and decoded back at home,” he says. “So it was a learning curve not only for the professionals but also for the [viewers], as well.”

Pray points out that the arrival of surround also put a new emphasis on crowd sound (something they shared with Disney, which also has come to specialize in crowd management).

“The real enhancement of 5.1 surround is how we capture crowd,” he says. “Because our philosophy is we want to make the viewer think they’re sitting in the stands, but with enhanced nat sounds. So I think that’s where the [impact] of surround: the base of your mix is that really big feel that you’re in a big place with a lot of energy, and then the effect sounds, the nat sounds add to that, feeling the bigness of the event and feeling the crowd swell in an organic manner.”

Integrating surround audio was a challenge in the studio and in the field, but the task extended to the other end of the wire, in viewers’ increasingly sophisticated — and complex — home theater systems.

“It was a double-edged sword because now the consumer had a home stereo/surround receiver that had a lot of hooks to it,” says Rousseau. “Sometimes [the device] would be in a sports mode or a theater mode, and then sometimes they wouldn’t be able to hear the announcer at all. And that caused us grief for a very long time. We would have reports written up weekly and we would track people down and surprisingly enough, show up on their doorstep near Bristol [ESPN’s Connecticut HQ] asking them what was the problem. And we would deduce the problem to be either a setup in the cable box, a setup in their TV, or a setup in their stereo system. So there was a lot of things going on at the same time while Scotty and everybody on the road was working to tweak the audio to the best sound possible while we were trying educate the consumer at home how to listen properly.”

Rousseau points out that the surround era also brought with it the new role of effects submixer on games, to manage a more complex array of sounds.

“All of a sudden you have more channels, you have more space, you’ve got more microphones,” he says. “In the early days, the A1 did everything: they mixed, they submixed. It was very cost-effective for us to have one person do everything. Once the complexity of the shows got bigger, that’s when the need for the subs arose.”

Adds Pray, “Besides adding a sub, technology has gotten to the point where you don’t have an A1 and an A 2 anymore. It is really a team with specialties developed inside the audio department because the technology is so vast and specialized; each piece of equipment has its own technological challenges as far as being able to operate at one time. Now, it gets even more complex where people are [working] at home, some in Bristol, some in Charlotte, and some on site. It all comes together as a team now.”

Immersive

Twenty-five years into the surround-sound era, most television sets are still stereo, although streaming and its use of earbuds and headphones offer ways for consumers without the budgets or desire for 5.1.4 or more-worth of speakers into immersive audio. Dolby Atmos-enabled soundbars are bridging some of that living-room gap but, as Strong flatly puts it, “What that comes to mind is the line, ‘If you build it, they will come.’ Broadcasters are getting there and the consumer will follow. I think that even a down-mix [of Atmos] still has more energy than some stereo mixes.”

Whether for a theme park or a ball game, Disney’s penchant for audio technology runs through ESPN’s own veins.

“Like with a transducer microphone that didn’t exist put on the back of an NBA glass [backboard] to hear that slam dunk, I’m just impressed by all the different concepts and ideas that keep coming out of here, whether it’s stereophonic microphones that didn’t exist a few years ago to the fact that viewers are watching on a phone or an iPad. I’m just intrigued to see what comes out of here and see what comes next,” says Strong.

Looking back, Pray sees a continuum from the 24-channel mono console he began mixing on decades ago to the 60-over-60-fader Calrec worksurface he mixes NBA Finals on, buttressed by scores of faders on his submixers’ desks, but adds, “That’s still not enough — I have to go layers deep. It was extremely simple in the beginning and it has gotten quite complicated now, but we grew through the process and I just think it’s going to be interesting to see where we go from here, what could be next. Just when we start to feel a little comfortable, then there’s a tug and there’s new and better things to do. So we really never rest. We are always developing and always growing. It’s been a heck of a ride. It really has.”